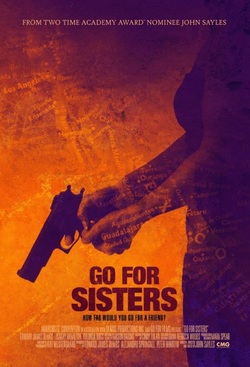

John Sayles Filmmaking on Go for Sisters with Edward James Olmos

Originally published in The Arts Fuse Magazine

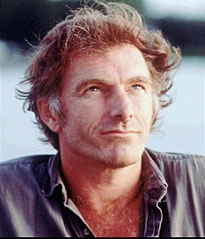

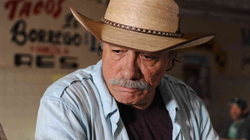

John Sayles is in his fourth decade as a stalwart of American independent film. He works with a writer’s skill, creating character-driven stories mixed with an actor’s instinct for shaping quality ensemble performances. I had the pleasure of working on Return of the Secaucus 7, and several other of his films for Mason Daring, his long time composer. Sayles has evolved as a director and an editor over the course of 17 films, sticking to his own vision as an independent artist. He has pleased and frustrated critics by his determination to make films with integrity and purpose. His latest film, Go For Sisters, was produced on a shoestring budget of under a million dollars—the cost for catering services on a big-budget Hollywood picture—and shot in 65 locations on a 19-day schedule. With a sharp script, an ensemble of superb actors led by by Lisa Gay Hamilton, Yolanda Ross, and Edward James Olmos, and bolstered by the rich cinematography of Kat Westergaard, the film is in many ways a return to the guerilla filmmaking style of his first landmark feature, Return of the Secaucus Seven. Every dollar is seen on the screen, and, as in all of Sayles’s films, there is a deeper social and political dimension at work. Though this film styles itself as a thriller and road movie, it is really a story of redemption. These are flawed characters who reveal layers of themselves as the narrative progresses. That story is about a no-nonsense probation officer named Bernice (Lisa Gay Hamilton) handling the case of Fontayne (Yolanda Ross), a recently parolee and former drug addict. We discover they were once friends and rivals, but when Bernice’s estranged son, Rodney, becomes a suspect in a murder involving human trafficking across the Mexican border, she enlists the help of her former friend in exchange for parole favors. Once across the border they enlist the further assistance of Freddy Suárez (Edward James Olmos), nicknamed “the Closer,” a retired cop who knows the ropes but is slowly going blind. The histories of these flawed characters are revealed as the movie gradually becomes a tale of redemption and self-discovery. It is the kind of writing actors love and that Sayles is celebrated for. I spoke with Sayles and Edward James Olmos about the genesis of the story. John Sayles: It started with two different ideas that I walked around with for about 10 years. One story was about two women who have been separated for long enough so that plenty of life has happened to them, and they are now really different people. There’s a question of whether they can find a friendship, but also whether they can find the person that they were back then—the person they liked—because they’re not so crazy about themselves now. The second story was about the disgraced detective who just followed the code, didn’t rat his friends out, but was the one that paid for it. He was kicked off the force. As a matter of fact, at one point I was thinking of calling the movie “Redemption,” from the Bob Marley song, but we realized how much it would cost to get rights to the song, so I decided to keep the working title. So though the story is an adventure, it’s really a study in which each of these characters has to risk something for somebody else in order to find the person that they like and admire within themselves. Arts Fuse: Can you talk about the structure of the story and the way these characters evolve? Sayles: One of the things I was trying to do was to tell the story and learn about exploring making things go backwards and forwards. So the two women don’t just talk about the old times right away. For the audience, and for them, there’s a series of revelations about their history—what kind of friends were they? How did they come to their present situations? And then there’s the forward story. I took a page out of Chinatown. The Chinese community has always been kind of mysterious in the United States, in whatever city that might be, San Francisco, Boston, or New York. So I used that kind of metaphorically. I wanted there to be something that remained a mystery. So there is another entire layer that remains unknowable. And so it is for the character of Freddy Suarez. No matter how much experience you have, you’re going to go into unknown territory. AF: It always fascinated me that in your film Limbo, set in Alaska, there was a wonderfully inconclusive ending—a rescue by helicopter in this case. We don’t know who is in the helicopter. The situation could conclude positively or negatively—and then the film cuts to black. Since then I have seen several films that require the audience to imagine a conclusion for themselves. Michael Haneke’s Amour and Jeff Nichols’s Take Shelter come to mind. Sayles: With Limbo, I asked the actors “what do you think happened?” And both of the men, David Strathairn and Kris Kristofferson, said, “Oh, I think they’ll work something out.” And both of the women, Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio and Vanessa Martinez, said, “They’re dead meat.” There was the possibility among the actors, not just the audience, to finish the story the way you see the world, perhaps. For me, the ending of the story meant this was a movie about risk. People stay in limbo because they are so afraid of hell that they are afraid to risk themselves—whether it’s a bad marriage, a bad political situation, or a bad job—and to go for heaven. In so many American movies it’s about whether the hero gets shot, or about whether he dies or not. I think it was the third Bourne movie, where David Strathairn plays the inside guy who goes bad—he didn’t know until he saw the movie whether his character lived, died, or was just wounded. I think they didn’t decide until they got into the editing room. It all came down to whether the character lives or dies. And of course that’s typical and expected. But I thought, let’s let audiences in on some of this. What’s their worldview? Maybe we should leave some of that up to them. AF: Getting back to the current film, can you talk about the setting and background of Go For Sisters--the California location and the incidence of Chinese smugglers? Sayles: It’s set in the San Fernando Valley north of LA and then on the California / Mexican border. About three years ago there was a woman arrested who had a little shop on Canal St., New York, and who lived very modestly. She turned out to be the head of the serpent, running a multimillion-dollar operation. That’s where all the money in smuggling into the country is now—in Asian people, mostly Chinese. They run a very different “coyote” operation. Some are going home because there’s not that much work here. But you’ve got this situation where the Chinese pay a lot more—$40-$50,000. And they’re guaranteed. You don’t get there and you get your money back. Or you get another try. Every year there are a couple of tunnels discovered in Tijuana, tunnels discovered that go under the border—Mexicali to Calexico. And it’s that particular border town that I worked into the story. AF: I recognize several of the actors from other of your films. Can you talk about the casting? Sayles: Yolanda Ross I met when she read for the part in Honeydripper that ended being played by Lisa Gay Hamilton and I remembered her. I met Edward Olmos at several film festivals and always wanted to work with him. Vanessa Martinez, who plays a fellow prisoner of Fontaine, I think this is the fourth movie she’s done with me. Martha Higareda, who plays the Mexican girlfriend, I worked with her when she was 16 years old in Casa de los babys. All are actors I’ve always liked and never got to work with—Héctor Elizondo, or Harold Perrineau, or Isaiah Washington. I just said “can you give me a day and work for scale?” Luckily a lot of them were available and willing to do it. AF: The community of actors that you put together and the quick shooting reminds me of what we did back on Return of Secaucus 7. That the lead characters are African-American really seems to be of no consequence. Sayles: The lead characters are only African-American because those are the actresses I really wanted to work with. They didn’t need to be. I usually don’t know what I’m going to cast. In this case I just started writing it and I realized I know who should play this. The same with Edward Olmos. And so all of a sudden I started defining who the other supporting actors might be, and the world that they would come from. This is a good part for Eddie. I have seen a lot of his movies and he is always a very different person. He’s a very physical actor. Think of him in Blade Runner, Stand and Deliver, The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez, or Zoot Suit--those are very different characters who move completely differently. I was thinking a lot about this older guy who’s losing his sight and can’t really drive anymore and wondering what Eddie would do with this physically. And he’s got such power. There are scenes where he just sits while there’s a major drug dealer walking around him. But you feel he’s still the guy with the power in the room. That’s a rare thing, for an actor to have that kind of power. Edward James Olmos: When John called and asked if I would help produce, I said yes immediately. It’s also a challenging piece of work for an actor. The script really defines the role, and with a well-written script the character jumps off the page. Playing a character with macular degeneration is a challenge for me and also for the other actors. I came in late to the shooting and the others hadn’t worked with me. I was playing a person who doesn’t make eye contact, which is something actors depend on. I was constantly doing something different and we really had to be in the moment. We were just thrown into it. They were terrific. AF: John, do you rehearse with anybody before you shoot? Sayles: I generally don’t like to rehearse. I do blocking rehearsals, but I don’t really like to have the actors, you know, “leave it in the locker room.” We started running the camera right away, so a lot of what you see is the shock of the new. It’s the first or second take. I give a bio to all the actors, and I give them the script, and we talk about character. Then I really just throw them into the arena and with each other. A lot of what you see is the actors just working it out within their characters. Sometimes you get some great surprises without them really changing lines, stuff I never would’ve thought of. AF: One last question: A lot of independent filmmakers look to you as a model. Where do you see the future of production and distribution of smaller independent films going? Sayles: It’s easier to make a movie now but it’s harder to get it distributed in a way that people will see it. I really don’t have any answers for distribution. Everything is changing so fast that even the people in the mainstream film industry can’t keep up with it. But for starting filmmakers—or a short story writer, or a novel writer—you can make something. It may not be with professionals. But you can make something and learn what you learn from it. And if you learn enough, maybe you’ll get to make it again with professionals, and with the actors you have always wanted. Given digital filmmaking and, quite honestly, people coming out of film school, and so much more information around than when we started in the late 70s, it’s possible to make a very polished movie. The same thing has happened in music. You don’t need to buy a lot of expensive studio time to make a good album anymore. We just need good players. We just encourage people—do something. Do a scene. Do the movie with your cousins. Maybe you’ll come back with a better digital camera and better actors. AF: Any project in the works? Sayles: I’m writing as fast as I can to try to get out of debt from having financed this movie. I’m doing a couple of rewrites on small features. Most of the work is in cable. Mostly the work what I’m doing is, I’m fixing things. When I’m lucky enough to get work, it’s mostly now in cable. Everybody’s trying to do a miniseries, the last six or seven years. And it’s much harder to come up with one of those ideas. |

Eddie Olmos

|