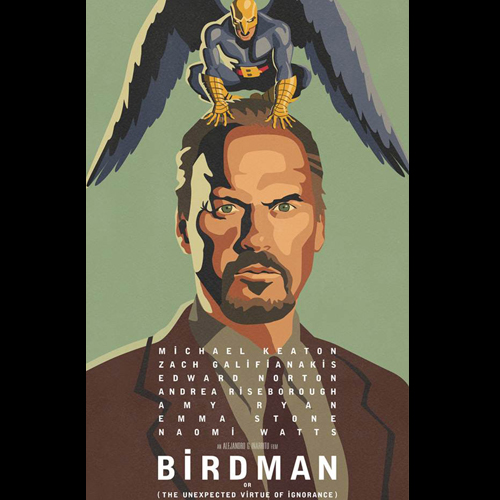

Birdman

|

Riggan Thomson, unlike the drummer of Whiplash, the year's other film about an artist who beats thimself to prove his worth, is his own sadistic taskmaster. Michael Keaton’s character in Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) lives on the thin line between hysterical delusion of grandeur and the sobering reality that he just might not matter. Riggan is an actor whose success in a series of “Birdman” movies has made him a global star. He decides to test himself by producing, writing, and starring in the Broadway adaptation of Raymond Carver’s short story “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.” In a style 180 degrees away from the snappy editing of Chazelle’s drumming movie, Mexican director Alejandro González Iñárritu has taken the audacious step of appearing to shoot the entire film in one long take. The shots took long preparation and required sustained and carefully choreographed blocking. At the same time the scenario leaps ahead chronologically, it segues methodically between reality and illusion. That contrast between the grounded tracking shots and a bevy of impressive special effects is perfectly suited for the jumble of ideas that the film raises.

Riggan is driven by his alter ego, which takes the form of the basso profundo voice of his “Birdman character.” (We can hear that voice as well.) We see Riggan levitating in lotus position in his dressing room at the beginning of the film. He can move (and throw) objects with the point of his all-powerful finger. It may look like reality, but the audience is firmly in the delusional, grandiose mind of its hero. But like many a successful artist, he is fraught with doubts and insecurities. Iñárritu’s screenplay is a dark and very funny send up of actors and their collection of woes and vanities. It comes off as a psychological version of the old Broadway farce Noises Off. Birdman is set backstage in a Broadway theater: the camera careens along hallways accompanied by a tumbling drum set score played by Antonio Sanchez (currently with Pat Metheny). This cacophony serves as an ironic contrast to the story’s emotional moments, which are accompanied by classical music. The camera veers in and out of dressing rooms and onto the stage for a rehearsal gone very wrong. It tracks around the bowels of the theater, spying out scenes worthy of a soap opera while fleshing out the cast’s convoluted relationships. When the camera finally snakes its way back to the stage the show is being performed, in a preview presentation, in front of a live audience. The camera will even soar into the sky and, in one steadicam shot bound to become a classic, Keaton runs through Times Square in his briefs.These are images straight out of dreams. It’s like Bunuel on steroids. What holds these hallucinatory proceedings together is a clever script performed by a first-class ensemble. Keaton is excellent in a part he appears to know well. He’s on camera often and rises to the challenge of pulling off some difficult and sustained emotional moments. Equally strong is Edward Norton as Mike, a vain, preening, but celebrated stage actor who has been brought in to save the show after the first actor is unceremoniously removed. The character requires a skilled actor who can play a performer who is gifted and comically pompous in equal measure. It is perfect casting. Naomi Watts is Lesley, Mike’s lover. She is desperate for recognition. Watts, who worked with Iñárritu in 21 Grams, played with this sort of nimble layering of reality and fantasy in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive in 2001, and has only gotten better. I’m less familiar with Andrea Riseborough as Laura, Riggan’s lover and the fourth member of the film’s stage ensemble, but the actress is strong, funny, and very sexy. Others in the cast include a slimmed down Zach Galifianakis as Riggan’s anxious manager. By playing the role straight, he gives a hysterical performance. Amy Ryan, who actually is a great stage actor, has a small role as Riggan’s warm-hearted ex-wife, a woman resigned to the man’s deep insecurities. Emma Stone as Riggan’s daughter, Sam, is just out of rehab and more than a little fed up with all the artifice of the acting business. Now working as his gal Friday, she provides her father with a dependably sobering perspective on his overweening vanity. In her world ‘getting real’ also means getting hip to Twitter and social media. (“Believe it or not, this is power,” she says when she shows him his now gone viral underpants-run-through-Time-Square video.) Once again this stunning young actress shows how effortlessly she can shift the tempo of a scene. She finds the heart, soul, and humor in a part that would probably have been a cliché in lesser hands. The movie is a mad, rambling mediation on illusion and truth, the insecurity and vanity of show business, the fatuousness of critics, the commercialism of Hollywood franchises, and the belief that popular taste “wants action, not talk.” For all its cynicism and bleakness, Birdman is filled with enormous humor and clever writing. It’s a tour-de-force of directing, beautifully shot by Emmanuel Lubezki (Tree of Life, Gravity, Children of Men), its images realized through an impressive assemblage of special effects wizards. You will see at the end why the movie is subtitled The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance, but watch carefully for the answer. You cannot predict this film’s elaborate twists and turns. While “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love” would seem to be an odd choice for the stage, that just may be what the film is really about. I had an acting teacher who once said that when you get down to it, no matter how complex, every scene at its core is always about love. |